| COMP3311 23T3 |

Prac Exercise 03 Schema definition, data constraints |

Database Systems |

Most recent changes are shown in red ... older changes are shown in brown.

Aims

This exercise aims to give you practice in:- specifying a schema using the SQL data definition language

- defining constraints on data

- loading tuples into a database

Note that, unlike previous Prac Exercises, this exercise will not explain how to do everything. Part of the aim of the exercise is that you explore how to use the PostgreSQL system. A very important tool for this is the PostgreSQL Manual. For this exercise, we will give pointers to the relevant manual sections; after this, we will expect you to go and find out how to do things yourself. There are 10 tasks in total for this Prac Exercise.

Background

We wish to build a simple database for a company which

has a number of departments. Each department has a manager and a

mission statement

, which is defined by a number of key words

(e.g. commitment

, service

, innovation

, etc.). The

company also uses numeric codes to identify each department. For

each employee, we need to know their name and tax file number (for

payroll purposes), and also the total number of hours that they work

each week. Employees may work in several departments, and the percentage

of their total hours spent in each department needs to be recorded; they

have to work in at least one department. Each department has a manager,

and they work full-time in that role.

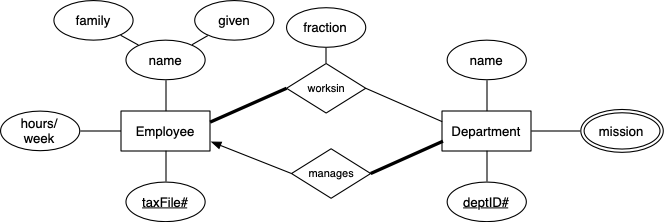

A possible ER design for this company is as follows:

|

Use this design as the basis for the rest of the Lab.

Consider now some facts about the company:

- there are three departments: Administration, Research, Sales

- Administration has department# 001

- Administration's

mission

is: innovation, reliability, profit - Research has department# 003

- Research's

mission

is: innovation, technology - Sales has department# 002

- Sales'

mission

is: customer-focus, growth - Administration is managed by John Smith, who works 40 hours per week

- Research is managed by Walter Wong, who works 50 hours per week

- Sales is managed by Pradeep Sharma, who works 30 hours per week

- Tom Robbins works 35 hours/week, half-time in Administration and half-time in Sales

- Adam Spencer works 50 hours/week mostly (90%) in Sales, and the rest of the time in Administration

- Susan Ryan works in Administration for 60 hours/week

- Steven Smooth is a full-time Sales worker (45 hours/week)

- Max Schmidt, Maria Orlowska and Yusif Budianto work full-time (40 hours/week) in Research

The following data, obtained from the Australian Tax Office (:-), gives tax file numbers for each of the employees noted above:

| Employee | Tax File # |

| Yusif Budianto | 777-654-321 |

| Maria Orlowska | 123-987-654 |

| Tom Robbins | 323-626-929 |

| Susan Ryan | 993-893-864 |

| Max Schmidt | 419-813-573 |

| Pradeep Sharma | 222-333-444 |

| John Smith | 123-234-456 |

| Steven Smooth | 632-647-973 |

| Adam Spencer | 747-400-123 |

| Walter Wong | 326-888-711 |

Exercises

-

Download the files.

There are several files available for this exercise, primarily:

-

schema.sql which contains a relational schema for the above ER design except that it is missing all of the constraints suggested by the diagram, and is also missing a number of common-sense or application constraints

-

data.sql which contains a collection of valid tuples to populate this schema, based on the above description, and satisfying all of the domain constraints

-

bad.sql which contains a collection of invalid tuples for this schema

To copy these files into your working directory, run the following commands in a terminal window:

$ mkdir -p ~/cs3311/prac03 # or choose another folder that suits (see note below) $ cp ~cs3311/web/21T3/pracs/03/*.sql ~/cs3311/prac03 $ cd ~/cs3311/prac03This will put the above files, plus a few others to use later in the Prac Exercise, into your working directory for this Prac. Once you've copied the files, change into the working directory (~/cs3311/prac03 or whatever you called it). Stay in this directory while you're working on this Prac.

Note that one of the files is soln.sql. This is a solution to the exercise. BUT try to resist the urge to look at this file before you've attempted the exercises yourself; you learn by attempting the exercise, not by simply reading the solution.

Tip: Most of the COMP3311 prac exercises require you to play with a number of files. It would be useful to create a separate subdirectory for each prac. Trying to maintain a single directory for all pracs will end up becoming messy, and there's always the danger of over-writing files with a common name (e.g. schema.sql). -

-

Create a new database to hold the company information.

Login to d2.cse.unsw.edu.au, start your PostgreSQL server, and use the createdb command to make a new database called company. More details on createdb can be found in the PostgreSQL Manual.

Tip: the d2 host is supposed to be dedicated entirely to running servers, such as PostgreSQL. It cannot also cope with hundreds of large applications like web browsers. The only things you need to do on d2 are: start/stop the PostgreSQL server and run the psql client. A useful way to set things up for your prac session is:- run a terminal app on d2 for psql

- run an editor (e.g. emacs, kate, ...) on the local workstation

- run a web browser on the local workstation to read this prac exercise

- in the editor and psql terminals, change into the same prac directory

- edit in the local window; test your SQL by pasting into the d2 window

-

Load the schema into the database.

In your d2 window, run the following command to load the schema:

$ psql company -f schema.sql

Reminder: the $ represents the prompt from the Unix command interpreter (shell). You should not type it. What you are supposed to type is shown in bold. Similarly, when we show what commands you are supposed to use with psql, the psql prompt will be displayed as company=# and anything you are supposed to type will be shown in bold.This should produce precisely four CREATE TABLE messages. As long as there are no messages containing ERROR or FATAL, things are working as planned. If there are error messages, read them, think about them, and try to work out what went wrong.

If you don't understand the meaning of the -f option, more details on psql can be found in the PostgreSQL Manual.

What this command does is to load a copy of the relational schema from the file schema.sql into PostreSQL's catalog. It also creates an empty instance of each table in the schema. You can examine the loaded schema via psql.

Just for fun, try to load the schema again by running the command:

$ psql company -f schema.sql

This time you should get a bunch of ERROR messages complaining about tables that already exist.

Note that schema.sql is a file containing a sequence of SQL statements (and some comments). One way of executing these statements on a database is via the -f command line option, as we have shown above. An alternative way of achieving the same effect is to

log in

to the database and invoke the file from within psql:$ psql company You should see PostgreSQL's intro message and then a prompt containing the database name company=# \i schema.sql ... which will give the same errors as above if you've already loaded schema.sql

You can examine the schema by connecting to the database in an interactive psql session:

$ psql company

and then using psql's meta-commands for studying the catalog. Take a look at the description of psql in the PostgreSQL Manual for details on the wide range of meta-commands available.

For this exercise, the most useful one is \d which allows you to get a list of tables, as well as examine individual tables.

Try the following commands in psql:

company=# \d Shows a list of tables company=# \d Employees Shows a schema for the Employees table company=# select * from Employees; Shows any tuples in the Employees table

After each command, try to explain precisely what you observed. Also, try variations on these commands (e.g. a different table).

Reminder: some students get confused about what to type where, and end up typing SQL commands to the Unix shell, or typing Unix commands to the PostgreSQL interpreter. If you see a prompt like $ or % or vxdb$, then you're talking to the Unix shell and SQL commands won't work (will give you some kind ofnot found

message). If you see a prompt like company=# or company=(, etc., then you're talking to the psql system for interacting with a database, and SQL commands will work, along with other commands like \d, etc. -

Load the valid data into the schema.

In your d2 window, run the following command to populate the database:

$ psql company -f data.sql

This will produce a bunch of lines of the form:

INSERT number 1

The 1 tells you that one tuple was inserted. The way our PostgreSQL servers on d2 are configured, number will always be zero.

If the PostgreSQL server was configured differently, you might see a unique number each time, which would be the object identifier (oid) of the tuple that was just inserted. PostgreSQL assigns a unique identifier to each object (tuple, table, view, ...) in the system. Despite the fact that object identifiers are not particularly useful at the user level, PostgreSQL tells you all of the tuple object id's anyway.

You can then return to an interactive psql session to examine the data in the database using SQL queries, such as:

select * from Employees; select count(*) from Departments;

See if you can answer the following questions using SQL:

- Which employee works the longest hours each week?

- What is the family name of the manager of the Sales department?

- How many hours per week does each employee spend in each department?

There's no need to write complex SQL queries to answer the above; just use simple SQL queries like those above to examine the tables and work out the answers manually.

-

Load the invalid data into the schema.

In your d2 window, run the following command to populate the database some more:

$ psql company -f bad.sql

This will produce the same response as before (INSERT lines), and add some more tuples into the database. The problem is ... all of the new tuples that were added from the bad.sql file are invalid in some way ... the database is now full of junk data, which you can go and examine via psql if you want.

How could the database system let us insert invalid data? Because we didn't specify any constraints on what the data should be like. Take another look at the schema and see how simple it is; it says nothing about primary keys, foreign keys, or more fine-grained descriptions of the actual data values.

Since the database is now full of junk, you may as well remove it and start again. Use the dropdb command to do this. Once again, the details of this command are available in the PostgreSQL Manual

-

Add constraints into the schema.

One of the most powerful aspects of database management systems is that they can help to protect you from putting invalid data into your database by checking constraints when each new tuple is added. Of course, they can't work out the constraints by themselves (if they could, we wouldn't need database programmers and we wouldn't be running this course). You need to define the constraints as part of the database schema. Details about constraints are available in the PostgreSQL Manual

The original version of the company schema contains no constraints at all, apart from very simple domain constraints such as:

- the Employees.hoursPweek attribute must be a floating point number,

- Employees.givenName is a string of up to 30 characters in length

- an Employees tax file number is an 11-character string

You should now think about what constraints need to be added to the schema in order to ensure that invalid tuples will be prevented from being inserted into the database.

Some of the missing constraints should be obvious to you from your understanding of how to map ER designs to relational schemas (e.g. missing primary key and foreign key constraints). The domain and

common-sense

constraints that we require you to add into this system are:- all TFN's are of the form 'ddd-ddd-ddd', where each d represents a single digit (Take a look at the PostgreSQL Manual for details on Pattern Matching and Regular Expression)

- every person has a given name, but may not have a family name

(e.g.

Prince

) - nobody can work more hours per week than there are hours in a week (each week has 7*24 = 168 hours)

- it is meaningless to work negative hours per week

- all Departments codes consist of exactly three digits

- two Departments cannot have the same name or the same manager

- the percentage of time that an employee works in a department must be greater than zero

- an employee may spend up to and including 100% of their time in a given department

Modify the schema.sql file and add constraint definitions all of the above (including primary key, foreign key and constraints to handle total participation).

Once upon a time (version 8.0), creating new databases on PostgreSQL was a very lightweight process. This may still be true on some installations of PostgreSQL (such as the one on d2) but does not seem to be true on all PostgreSQL installations. them. If creating databases is fast on your PostgreSQL server, you can use the following approach to iteratively check/load your new constraint-rich schema:

$ createdb company $ psql company -f schema.sql Produces error messages. Fix schema definition using editor in other window. $ dropdb company $ createdb company $ psql company -f schema.sql ...

If creating databases is slow in your PostgreSQL installation, you may find that the above approach wastes too much of your time. To help get things done quicker, there is a small SQL script called drop.sql that you can use to clean out all of the tables from the database and effectively

start again

with a fresh database. This means that the way to iterate towards a solution is something like:$ createdb company ... You only need to do this once $ psql company ... company=# \i schema.sql Produces notices about creating tables, etc. along with error messages if there are problems with your schema definition. company=# \i drop.sql Produces a bunch of DROP TABLE messages May also produce ERRORS if some tables weren't created above These ERRORS can obviously be ignored company=# \i schema.sql Produces notices about creating tables, etc. along with error messages if there are problems with your schema definition. company=# \i drop.sql ... Continue like this until the schema loads successfully i.e. until \i schema.sql produces no ERROR messages

Tip: Because of the way PostgreSQL's parser works, it is sometimes not possible for it to tell you precisely where an error has occurred when you're loading schemas. Sometimes, the line numbers in the error messages refer to the line immediately after the line containing the error. In other cases, they refer to the end of the table definition (which indicates simply that there was something wrong in the table definition). Occasionally, they will actually pinpoint the exact line where the error occurred, but mostly it is one of the previous two cases. Use the syntax diagrams from the PostgreSQL manual to work out exactly what you've done wrong if you get errors. This aspect is not a bug in PostgreSQL; it's simply a fact of life with Yacc-based parsers (see COMP3131 for details). -

Load the valid data into the new database.

Once you have successfully loaded the schema, run the following command to populate the database:

$ psql company ... company=# \i data.sql

This worked ok before, when there was no constraint checking, but you may be distressed to find that it now generates errors. Think about the dependencies between tables and work out how to rearrange the statements in the data.sql so that the data can load ok.One way to approach this task would be to follow this sequence of steps until you get all the data loaded successfully:

$ createdb company $ psql company -f schema.sql $ psql company -f data.sql Produces error messages. Fix data.sql using editor in other window. $ dropdb company $ createdb company $ psql company -f schema.sql $ psql company -f data.sql ...

As noted above, this approach is too slow on some PostgreSQL installations, so you can make use of a file clean.sql which removes all of the data from the database, leaving just four empty tables:

$ psql company ... company=# \i data.sql If it produces error messages, fix data.sql using editor in other window company=# \i clean.sql Produces messages about deleting tuples company=# \i data.sql Repeat until this step produces no errors ...

Once you've loaded the valid data successfully, you're ready to deal with the invalid data.

Side note: Try changing the order of the delete statements above. What happens? Can you explain why?

Side note #2: You might like to think about the difference between drop.sql and clean.sql. The first completely removes all of the tables from the database. The second removes all of the tuples and leaves four empty tables.

-

Reject attempts to insert invalid data.

With all of the valid data still intact, you should try to insert the invalid data via the following command:

$ psql company ... company=# \i bad.sql

Since every tuple in bad.sql is invalid in some way (assuming that data.sql has already been loaded), you should see only ERROR messages. If you see any INSERT messages, then your constraints are not correct.

Repeat the following steps until you finally achieve rejection of all of the invalid tuples:

$ psql company ... company=# \i schema.sql Produces notices about creating tables, etc. company=# \i data.sql Produces INSERT messages; loads valid data company=# \i bad.sql If it produces any INSERT messages, your schema is incorrect, so you should use a text editor to change schema.sql company=# \i drop.sql Produces DROP TABLE messages; leaves empty database company=# \i schema.sql Produces notices about creating tables, etc. company=# \i data.sql Produces INSERT messages; loads valid data company=# \i bad.sql ... Continue like this until your schema is correct i.e. until you receive only ERROR messages from \i bad.sql

Once the output from the psql command

company=# \i bad.sql

consists entirely of error messages (no inserts), you have provided sufficient constraints to ensure that only valid data can be inserted, and your prac exercise is complete. -

Challenge: tricky constraints #1

Here's something to think about if you found the above exercise too easy.

Exercise: Consider how you might implement the following constraints:

- no worker can have more than 100% of their time allocated

- a manager must spend all of their time in just one department

To test these out you'll need to try to insert additional tuples that violate these constraints. For the first case, you could use the following insertion:

insert into WorksFor values ('747-400-123','001',10);For the second case, I'll leave it for you to work out a suitable test.Hint: you'll need to use PLpgSQL and triggers which we'll discuss in lectures in a few weeks.

-

Challenge: tricky constraints #2

Consider a variation on the above ER design, where each employee works for exactly one department:

Think about the changes that this would make to the relational schema. In particular, now that the relationship between Employees and Departments is n:1 rather than n:m, the WorksFor table would be replaced by a non-null foreign key in the Employees table (non-null since every employee must work for one department).

Modify your schema so that it correctly implements the new ER model and then try to insert some data. If you made the modifications correctly, you'll discover that you have a problem ... You cannot insert an Employees tuple until there is a Departments tuple for them to be associated with. However, you cannot insert any Departments tuples until you have an Employees tuple available to be the manager of the department.

How can this be resolved?

There are two possible approaches:

- remove (some of) the constraints associated with the Employees.worksFor attribute or the Departments.manager attribute. This would allow you to insert either Employees tuples or Departments tuples without insisting on the existence of the other. Of course, doing this would mean that you've removed some of the semantics implied by the ER model (employees must work for some department and departments must have a manager). Once the database is populated, you could add the constraints in via the alter table command, but any invalid data that you'd already added would remain. Also, if you ever needed to add a new department which is managed by a new employee, you'd need to remove the constraints again, make the additions to the database, and then restore the constraints.

-

A better approach is to realise that the insertion of a new employee

and a new department at the same time needs to be treated as a single

operation, and that constraint checking simply needs to be delayed

until both tuples are inserted. If the coinstraints are satisfied

with both tuples added, then the operation is successful. If the

constraints are not satisfied, then both tuples should be removed.

The approach of treating multiple updates as a single operation is

known as a transaction.

PostgreSQL has a method for specifying that constraint checking should be delayed to the end of a transaction which is described in the section on deferrable constraints in the documentation on the create table statement, and with additional explanation in the set constraints documentation. You'll also need to read the doumentation on begin and commit to work out how to implement it. (You can also find an explanation of this in the last couple of questions in Exercises 03).

Exercise: Try to implement both of these schemes for handling "mutually dependent" foreign key constraints.